My Dad, the Running Man

Dad died while out on a run 27 years ago. I still miss him. This story is a tribute to him.

He holds nothing back from life; therefore he is ready for death, as a man is ready for sleep

after a good day’s work.

-Lao Tzu Tao Te Ching

I’d seen dead bodies before but never anyone I knew. So when I entered my father’s room to see him I asked my sister to come in with me. She had been with him for a few days and was used to seeing him without life in his body. My three brothers and she had gone to the morgue with his best clothes, dressed him and brought him back home for a last family reunion. Now when I arrived he was lying in his casket, on his bed for his final sleep. A sheer cloth covered his body so that he looked mysteriously distant. Oh no, no, Dad. This can’t be. Not you. You are supposed to be indestructible. I asked my sister to take the cloth off. I wanted to see for sure that it was he, to look him face on but I couldn’t do it myself. The veil between life and death was lifted. It was Dad’s face, pale, waxy and cold, his hands gently cupped by his sides. I looked closer. On his forehead was a floret of skin and blood where he had hit the ground. I waited, looking hard for a twitch in his fingers, a glimmer of a smile on his lips, a flare of breath in his nostrils. I half expected him to suddenly jump up and laugh, ‘just kidding!’ Nothing. Dad was dead.

* * * * * * * * * * *

My father, Gordon Moller, was born in Hawera in1925, the fifth child of eight. His father taught his boys to box, and Gordon was fighting in tournaments from the age of ten. His boxing career might have taken off but the war came along and Gordon, eager to join his older brothers in fighting for freedom, turned his year of birth from 1925 into 1923 and signed up. When his father found out he gave young Gordon a kick in the pants and a pat on the back at the same time. At the age of sixteen Gordon was on a warship headed for battle in the Coral Sea.

I cannot imagine the horrors that a teenage country boy from New Zealand witnessed. Piecing together stories from Mum, and the odd snippet from Dad himself, I can only conclude that his leap from childhood into the adult world was too high, too wide, too deep. In the next five years before he was twenty-one, Gordon saw action, destruction, death, cruelty and depravity.

It was not just his ability to deliver a fast, fat, well-placed wallop that earned him the nickname of “Punch Moller” in the navy, it was also that his idea of a good time was a “decent bloody scrap”. My mother tells me that at this time, while at port in Auckland, he got in a fist fight with a Yank and beat the guy up so badly that he almost killed him. Gordon was put in Mt Eden prison while they waited to see if the American would pull through. He did and Gordon was released. Meanwhile his ship, the Leander, had moved to another port and when Gordon caught up with it he was disgruntled to find that his post on the 4 inch gunnery had been reassigned to another sailor. Gordon had earned that position by topping his class in target shooting and he was loath to be put on the other side of the ship in what he considered a lesser post.

A few weeks later during a battle with Japanese naval forces for occupation of the Soloman Islands, the Leander was torpedoed, and the reassigned sailor sitting at Gordon’s former post was catapulted overboard by a torrent of water that rushed to fill the vacuum created by the blast, never to be seen again.

In cleaning up the ship after the bombing, Gordon was assigned, along with others, to mop up the damaged hold. In his later years Dad had confided to my brother that as he reached into the watery soup to pull out debris, he realised that the slimy mess in his hand was a decaying spinal cord still attached to its backbone. This was just one memory that haunted his sleep for the rest of his life.

With the Leander out of commission Gordon transferred to England where he joined the British Navy aboard the HMS Bulldog, which sailed in the North Atlantic convoys. This destroyer was one assigned to escort supply ships through enemy waters to the Russian port of Murmansk on the Arctic Circle. The rate of attrition on these voyages was horrendous with enemy attacks and heaving waters that would freeze you to death in minutes.

But most frightening for Gordon was the witnessing of younger sailors being raped on the deck down below by seasoned homosexual predators. From that day on till the day he died, Gordon always slept with his back to the wall and his face to the door. Dad never told me directly of this. I read it in a confidential doctor’s report that was found in his personal belongings when he died.

* * * * * * * * * *

When the war ended it is no wonder to me that Gordon was disturbed, restless, guarded, and probably always somewhat sleep deprived. My mother tells me that he refused education and skill training offered to ex-soldiers. Instead he took a job driving a tanker for the Plume Petroleum Company.

It was midnight and Gordon had made a late night run to deliver petrol to a sheep station in the back blocks. On his way down a long hill he fell asleep at the wheel. BANG! BANG! BANG! Gordon was jolted awake as he careened into the tiny township of Apiti and skittled three petrol pumps of the town’s only station. The fourth pump, the Plume pump, he loyally missed as the runaway truck swerved and rolled into a bank. Gordon lay there mashed against the window, dazed. Then, from above, the door opened and a voice called in,

“You okay, mate?”

“Yeah, I’m okay.”

The silhouette reached a hand in and hauled Gordon out. The man leapt into the truck, fiddling around under the dashboard in the dark.

“Fall asleep did ya?”

“Yeah? Yeah, yeah…. Guess I must have.” Gordon was still stunned.

“Well best you tell ‘em your light went out. They won’t think to ask if it was yours or the truck’s,” he chuckled as he climbed out of the cab.

By this time people were beginning to gather. The local cop pulled up, sizing up the moonlit mayhem as he got out of the patrol car.

“Lights went out.” Gordon volunteered, shrugging his shoulders. The cop jumped in the cab.

“Lights are gone alright. Looks like a wire came loose. You’re one hell of a lucky fella. It’s a wonder you weren’t blown up in this thing.”

Gordon turned to wink to his mystery helper, but he had slipped back into the shadows from where he had come.

After that Gordon ‘went bush’. He had been carrying a gun around with him and the impulse to put it to his head and be done with this mess of a life was gripping him. Now alone, he attempted to reorganise his damaged psyche into some kind of operating normalcy. Time and nature are great healers, and Gordon had a great will to survive. After a year he finally lay down his gun and reemerged into society.

Mum tells me he took lousy jobs from lugging rolls of wire around his neck and stacking them, to hauling frozen cow carcuses at the abbatoir with sacking on his feet (grips well on a bloody floor). None of these jobs lasted long. It wasn’t until he married my mother, bought a house and a shop in the small town of Putaruru, quit a fifty-cigarette-a-day habit cold-turkey and started a family, that he finally settled down.

* * * * * * * * * * *

When my 5 siblings and I were growing up we knew that Dad was difficult. He had dark moods and we did our best to avoid him during these times. Inside him some deep troubles would churn. Then some incident would catalyse this brew to a simmering, violent anger and Dad would come at you, not with his fists, but with nasty demeaning criticisms that stuck you to the marrow. Often our mother took the brunt of it, but we all copped our share.

These episodes shadowed the good memories I had of my father. For a long time I forgot that it was he who took the family adventuring for a year around Aussie when I was just three, sleeping in the car and a blow-up lilo under the stars. When my third brother was born on a stopover in Brisbane Dad left Mum in a little house with her brood of five and went off up north to cut sugar-cane to support us.

When he returned I had shingles. At three and a half years old I was the youngest known case of this nervous disorder which left me with a ring of sores around my waist. I had forgotten that with my mother tending to the baby that it was Dad who tended to me. Every night he painted my belly with the prescribed medicine. In the morning I would run out to the kitchen trailing the sheets which were stuck to the scabs on my waist. Dad would lift me onto the table and give me the command to start screaming. Only when it reached a convincing pitch would he rip the sheets off me. I know it must have but I can’t remember it hurting. I loved that routine. Then I would go out and play while Dad did all the washing; sheets, nappies and the rest, all by hand, in a big concrete tub.

I couldn’t remember how he would pack all seven of us in the Holden station wagon and go on safari to the sea at Mount Maunganui, or to the mountains at National Park to snowsled on plastic bags, or to swing on the vines as we beat our chests with a Tarzan call in the native bush at Fitzgerald Glade. I couldn’t recall that he would steal away our Disney comics to read them first and preferred Donald Duck to Mickey Mouse. No, it was those little toxic darts of derision and blame, grown septic over the years, which had dominated my thoughts of him.

When I was five I needed to be hospitalised. There was no way I wanted to go. So Dad promised to take me to the doll factory on the way and buy me any doll I wanted. Since he now owned a successful toy shop in our town, he probably figured he could get two lots of business done that day. I relented. This was my big chance to get the walky-talky princess bride doll I coveted so badly. At the factory I chose just that, and Dad talked me out of it. Instead he suggested a small rubber doll. I gave in. I was no match against my all-powerful father and I knew it. I never got the doll I wanted and I held it against him for 36 years.

Over the next few years I observed my father; surly, mean, sometimes drunk, demeaning my older brother and fighting with my mother. At those times I hated him.

* * * * * * * * * * *

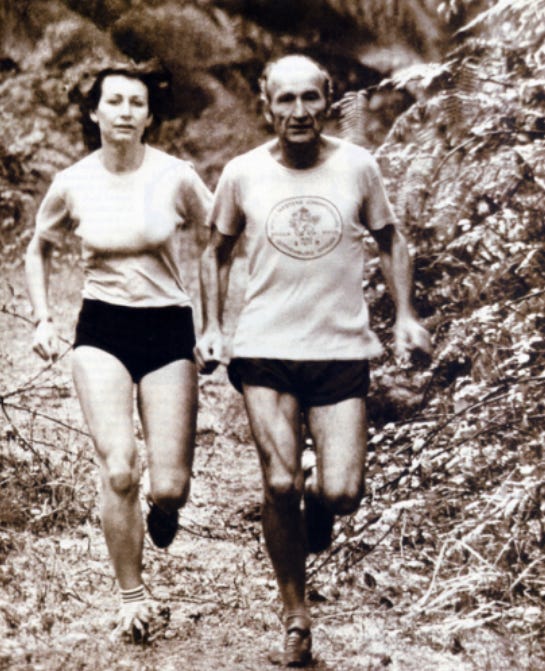

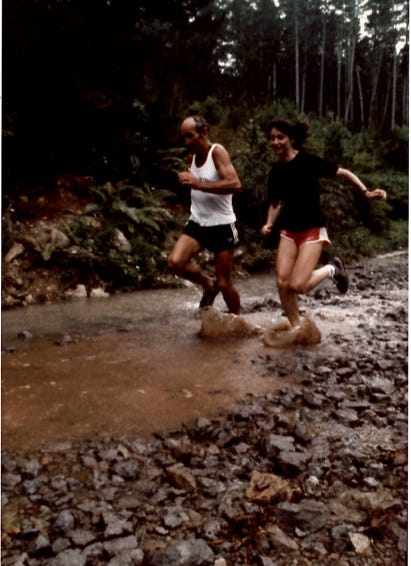

Then when I was 13 my relationship to my father changed dramatically. We started running together. I was a promising youngster, and Dad wanted to get rid of his middle-age beer gut. Off we went night after night for our run, working our way from laps around the park, to the four and a half miles to the end of Overdale Road and back, to long runs of several hours in the Pinedale Forest. Dad figured he was my safety valve, and if he couldn’t hack it, then it was too much for me. He was no theorist but his homespun sense of things saw me through more than any textbook formulas. He said that a good run cleared the phoo-phoo valve and insisted whenever I fell or sprained my ankle to get up and keep running. When you could run a two hour run in one and half hours then you were getting fit. Running on rocks made you nimble, uphills made you strong and the finishing sprint made you fast. His well-worn motto was “to hell with the submarines the convoy must go through.” I didn’t know what a convoy was then, but I did know it meant put your head down and get the job done. Willpower.

With Dad leading we ran every dead end in the forest, probably twice, we forded streams, ran up cliffs, stepped in cow-pats, dodged logging trucks, often got lost, and always sprinted each other to the finish. I always won the sprint except when Dad managed to trick me into taking a wrong turn. When it was pouring rain we went out and ran barefoot in the park, skidding through the puddles trying to knock each other over.

One day an American woman who had run in the world Championship cross-country came to run with us. Being shy of women runner role models at fourteen years of age I was in awe. We took her to the forest on one of our best runs. About a mile into the rocky surface she was lagging a little and then suddenly burst into tears and demanded that her husband carry her back to the car because her legs were getting ruined. My father, concerned that this role model had demoralised his impressionable daughter, later explained to me that he had since found out that all Americans ran on golf courses that had been smoothed by bulldozers and that they always wore over-cushioned shoes that couldn’t feel the ground and made their legs soft. We were so much better off, he explained, because we ran on anything, wearing just our canvas tennis shoes or barefeet.

We had miles and miles of fun and we talked and talked. After a few thousand miles his goofy stories began to repeat; pouring a beer down the biggest meanest GI’s back to start a fight, stealing the policeman’s car for a ride home after a night on the booze, Why did Mickey Mouse leave home? Because he found out his old man was a rat. I acted like he was silly but really I loved it. My father had become human.

* * * * * * * * * * *

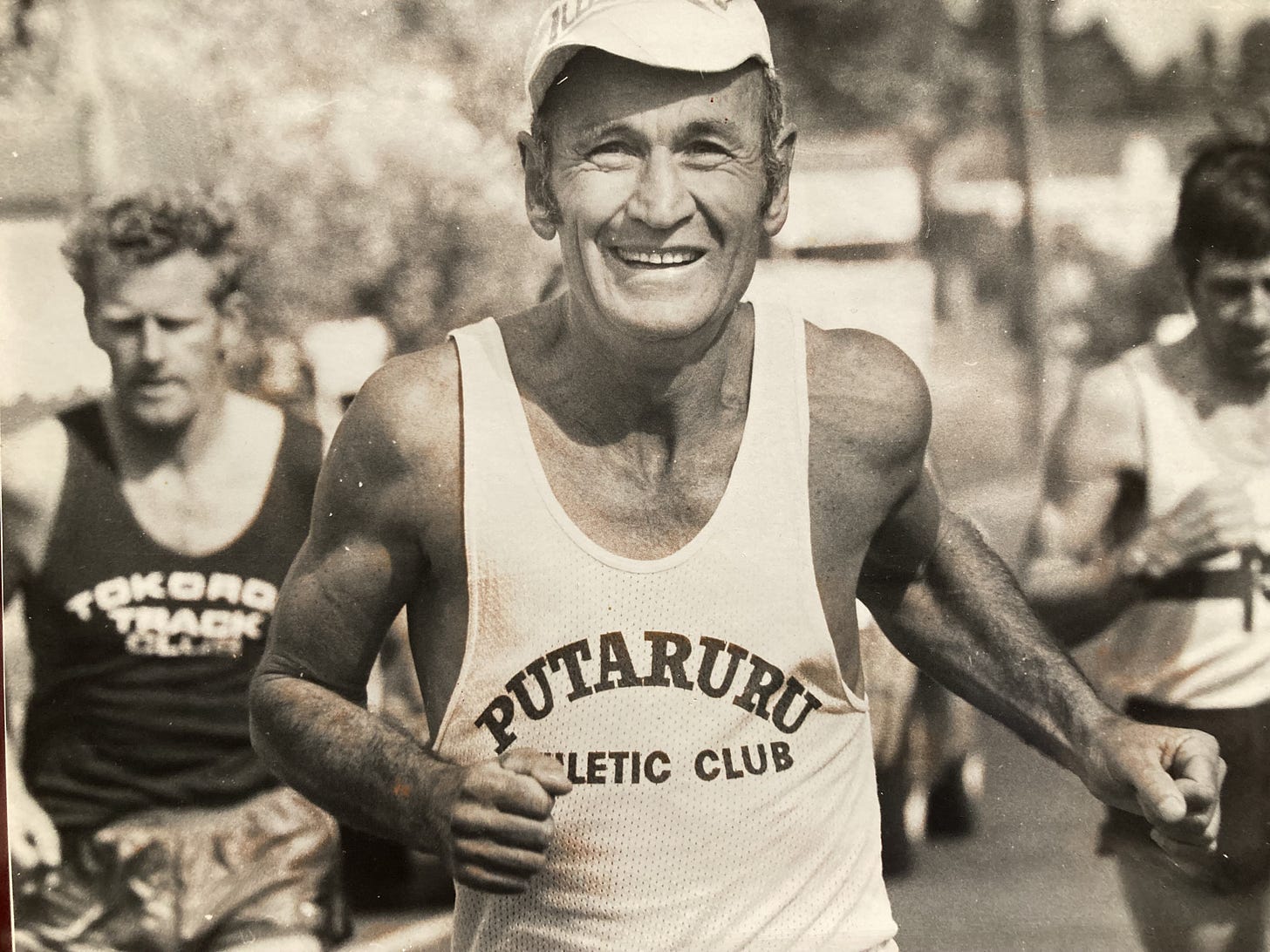

For a long time Dad would not race. He said I was the star and ‘being on show’ was not for him. Then one day the club recruited him for a road relay. He was hooked. Now we went to races together and cheered each other on.

It was a cold wintery day and we were running cross-country way out in the wop-wops, as Dad would say. My little brother and I ran our races and stood on the sideline to cheer Dad on in the veteran’s race. These races were not for the faint-hearted. The race field was mostly scrawny old guys like mountain goats who threw sheep around all week and on weekends raced their knarly lean bodies over muddy, hilly farmland. Watching the first lap I was amazed. Dad looked great and was way up at the front. On the second lap he had dropped a few places and didn’t look quite so hot. He was starting to look more like the submarine going to hell than the convoy. On the third and final lap he didn’t arrive. I waited. A search party went looking. No sign. It was getting dark and I was feeling panicky. A man came running over. “He’s found,” he announced, “he was just at a neighbouring house taking a bath.” The search party nodded as if this was a perfectly normal thing for someone to do in the middle of a race. Someone dropped my Dad off at the hall and we went home.

Dad did not look well. He said that during the race he was running much faster than he had run before. On the third lap he felt that he was invincible. When the other racers changed direction, Dad kept going straight ahead, off the course. Faster, faster, faster was all he could think of, no longer aware of the race or where he was. Over the paddocks, through fences he ran, on! on! on! like a bad Hash House Harrier advertisement. Eventually he passed out. When he came to he managed to crawl to a farmhouse. No-one was home, so he drew a big warm bath and jumped in, Goldilocks-style. Feeling better he picked up the phone. It was a party line and two women were talking. Where am I? he asked. They figured it out, picked him up and dropped him off at the hall.

This was the first of many episodes. A cardiologist said it was his heart and that the enzymes in his blood indicated he was near death that day. It didn’t change a thing. Dad was out running again in a few days

Then one day Dad didn’t come home. He had gone out for a run early in the afternoon in the forest. Now at 10 p.m. my concerned Mum called the police and a search party was organised. The local doctor got out of bed to lend his services. Dad had been to him the day before for a sore leg for which the doctor had prescribed rest. That was not acceptable. After some negotiation a settlement of “short runs” was reached. With this information the search party covered all the short loops. It wasn’t until 3.30a.m. when he was discovered on the eighteen mile loop. It was winter, and by now it was bitterly cold and raining. Hearing voices Dad leapt from his burrowed hollow in the ground, where, covered with ferns, he had sat shivering waiting for dawn. When he arrived home he invited everyone in and insisted on making them all tea, giving special sheepish attention to the doctor. Then once they’d left he told my mother off for calling the police and making a fuss.

* * * * * * * * * * *

I left home for university at seventeen. I ran, I studied and I rebelled against my parents so carefully that they didn’t notice. Occasionally I brought home boyfriends with long hair and earrings who couldn’t keep up with my Dad on a run. Dad referred to them as “dogs just sniffing around” and scared most of them off. Secretly I was pleased. If they couldn’t stand up to my father, I no longer wanted them anyway. The truth was there was not much emotional room for boyfriends. I was too busy constantly seesawing between trying to please my Dad and being pissed off with him. Try as I did I could never seem to make him happy but we could sure make each other mad as hell.

When I left to live overseas I thought I would be free. But blood bonds defy time and space and I missed my father dearly. So one night I decided to do the unthinkable, to ring my father and tell him I loved him. As we chatted I gathered myself for the big plunge.” I love you Dad”, I blurted. Stunned pause….”Well so you bloody well should,” he replied. End of conversation.

While I was galloping up and down the golden American roads, back in New Zealand Dad was fast becoming a running addict. He sold his shop and with steady rentals from his real estate investments he now had time to train twice, sometimes three times a day, in his newfound career as a marathon runner. And he was good. His best was 2 hours and 51 minutes, run when he was well into his fifties. He broke 3 hours so often that all those who aspired to break that barrier would tag onto the back of my Dad as their best bet of doing it. Soon Dad became an international athlete like me, travelling the globe going from race to race. Every so often he would show up on my doorstep in America with his running shoes on, a small kit bag and always a great tan, itching to go for a run.

It was on one such trip to Boulder that I realised how disturbed Dad was. One night I was awakened by terrified yelling coming from the next room. “No! No! Get out! Get out!” As I looked into the room Dad was on the bed against the wall, fending off his invisible attackers, bashing his pillow so violently that it had burst and feathers filled the room like a fresh snowfall.

When Dad was in his sixties and looking for new challenges he decided to try triathlons. First he had to learn to swim. Doing so nearly killed him and did kill his running. Taking lessons in the tidal pools while visiting my brothers in Sydney he swallowed so much polluted water that he developed pneumonia. At this stage my brothers and sisters had all left home, and my Mum, finished with child-raising, decided she was also finished with coping with his moods and nightmares, and left my Dad to have a life of her own. Dad was living all alone and now back in his part-time retirement home at Snell’s Beach, he was deathly ill.

Hardly able to move, and drowning in his own fluids Dad later told me that he lay on his bed in a dark and horrifying hallucinogenic world. Round and round and round in the darkness, swirling through space, endlessly. An elegant ebony hand that ended with a smooth gold bracelet at the wrist would swirl towards him and attach itself to his throat and squeeze the breath out of him. With all his might he would fight it, wrench it free and fling it out into the void, and then like a boomerang it would make its way back to his neck. He struggled in this hell for five, six, seven days, and then from somewhere distant a voice, an oddly familiar voice like that of an old friend, told him to get out, get help.

Somehow he made his way to his car and drove on winding busy roads to my little sister’s house in Auckland, some 60 miles away. His only recollection of that trip was the car horns of other traffic with which he used to navigate his way. When Dad arrived, my sister was appalled. His clothes were hanging off his emaciated body, he was incoherent and coughing blood. With treatment he recovered but he never really ran again.

After that he mellowed, as if he no longer had the energy to sting hard. Alone, but alive, he began to ask questions, What’s wrong with me? How did I end up like this? What did I ever do to upset so-and–so? Sometimes he would badger me for answers.

One day he wanted to know why my older brother didn’t make time for him.

“Have you asked him?”

“Yeah, but he won’t talk to me. You kids are all the same. Just like your mother. Can’t get you to talk to me.”

“Well you were pretty mean to him when he was a kid.”

“Rubbish! I did lots for you kids!”

“Of course you did. That’s not what we’re talking about.”

“Well how can I do anything if I don’t know what’s wrong.”

“So why don’t you ask him? How can you know if you don’t ask.”

“I did.”

“So what did he say?”

“He said I didn’t ever tell him I loved him.”

“Well then, did you tell him you loved him?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Well I’m a kiwi bloke, aren’t I?”

“Have you ever told anyone you loved them?”

“No.”

“Well then it’s time to start. Do you love me?”

“What sort of a question is that?”

“A simple question. Come on, do you love me?”

“Of course I do.”

“Then tell me.”

“You know I do.”

“Then say it.”

“I do.”

“No, tell me you love me.”

“Yes I do.”

“No, say, I love you.”

“Yes that’s what I’m saying.”

“No, say the words.”

“Okay, okay.”

“Well come on.”

By this time he was giggling in a giddy, teenage sort of way.

“Okay then I’m going to say I love you, okay?”

“Well then say it.”

“I just did.”

“No you said you were going to say it.”

“Well I said the words.”

“So say them again.”

“ Okay so you want me say I love you. Okay?”

“No. Cut all the other stuff. Just say, I love you.”

“So I’ll just say I love you.”

“Not good enough.”

“ Okay, I love you, okay.”

“Now that wasn’t so hard was it? I love you too.”

The end of our conversations after that had a new protocol. Dad ceased to sign off with the question, “Anyone you want beaten up?” and instead would ask, “Anything else?” and we would launch into our tell-me–you–love-me routine. Soon he was doing it with my brothers and sisters. I began to worry that Dad was getting to the end of his life because he was starting to get nicer.

* * * * * * * * * * *

We had our last big stand-off a year before he died. I had struggled so hard to make the last Olympics and my body was falling apart. Dad kept writing his advice to me which I took as personal criticisms. You take too many vitamins, you have too many bludgers hanging around you, you’re not trying hard enough. His letters would send me into orbit and I would fume for days over them.

After my less than mediocre Olympic finish, Dad wrote that “I was a dried up old corn cob surrounded by mothy types.” He had a way with words. I wrote back that he was “a miserable old coot with a poison pen”. He wrote back to say he was “only speaking figuratively”. I didn’t write back.

When I arrived home for Christmas he showed up to where I was staying, nothing was said about the letters. We had made up many times and it was better just to get on with it. He had a long box and by the smug way he watched me open it I knew it was something special. Inside was a princess bride doll, the most beautiful doll I had ever seen.

During this visit officialdom in New Zealand Sports hosted a luncheon in honour of my achievements in athletics. Dad attended and listened intently as I was applauded by the very organisations that I had often batted heads with in my earlier days. Of all the acknowledgements I had received this was probably the sweetest. Afterwards Dad told me how proud he was of me. When I heard him say that I realised what I had been running all those years for. Here was my gold medal out of the mouth that had wounded so many times, and finally I felt free to stop competing.

Then quietly but clearly he added, “I’m sorry for calling you whatever it was.”

“You called me a dried up old corncob,” I bristled.

“Really, did I say that?” He sounded quite impressed with himself.

“Surrounded by mothy types,” I added.

“Well, I’m sorry if I hurt your feelings.“

I was taken aback. “Now that I think about it I think it’s kind of funny”, I conceded, “… and true. I was dried up. I’m sorry for calling you a miserable old coot.”

“Well”, he said “maybe that was true too.”

A few weeks later my hometown of Putaruru opened the Lorraine Moller Reserve, a gully just a stone’s throw from our old family home, which was to become an arboretum of exotic trees. I planted the first one at the opening ceremony. Dad was quiet. Usually domineering at family gatherings, this time he took a backseat and seemed thoughtful and uncharacteristically gracious. There was certain sadness about him and I thought that as he stood by my mother with his arm around her waist for photos in front of our old home, that he was full of regret and really missed her.

The last time I saw Dad was a month later. I was about to return to my home in the States and drove up to spend a few days with him. This time instead of badgering me for why I hadn’t made more time for him, he seemed genuinely grateful for the time we had. He took me on his two hour walk to a new steep track he had discovered, a real grunt of a climb just the way he loved it, and he even beat me to the top (though he tricked me because I didn’t know we were racing.) On the way back we stopped at his tree stump and did exercises, as was his daily practice. Whenever we met there was always something special about doing this routine together as we had when I was a teenager. This time both of were slow but that didn’t matter, together this Dried Up Old Corncob and the Miserable Old Coot felt at home doing what had been the makings of both of us.

We spent time talking, really talking. There was no resistance from either of us. I felt it was the first time I had ever really listened to him. He wanted to make his peace with all the family. He would go down the list one by one, making assessment of their lives, how he stood with them, how he could help them. He told me what was in his will and where he hid his cash and the keys to his house. It was starting to scare me.

“You sound like you’re planning to kick the bucket?”

“Well you never know,” he shrugged.

“Nonsense,” I rebutted with great authority. “You’ll be like Grandad, live till a hundred. It’s in your genes.”

Dad shrugged his shoulders. “I’m lonely here and it gets so quiet, but I do have company. This fellow keeps following me around the house trying to get my attention. He’s got very persistent lately.”

“What sort of fellow?” I couldn’t see anyone…... “You mean a spirit?”

“Yeah.”

“Really? You’re not kidding?” I could tell by his face, he was serious. “So who is he?”

“I don’t know. He’s quite engaging really, I quite like the chap, but I just try to ignore him.”

A few weeks later Dad wrote to my mother saying that the Grim Reaper was at his shoulder.

When I left that morning Dad stood on the curb by his house waving goodbye. I drove off and then impulsively I stopped and reversed back to where Dad was still standing. He leaned into the car.

“It might be your last chance,” I said.

“I know. I love you.”

“I love you too,” I replied and we both cried. This was the first time I had seen a tear from my father and I cried all the way back to the airport.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Three months later. The phone rang persistently. I heard it in my sleep and refused to get it. We had a boarder who specialised in overseas boyfriends and I assumed it was one of them who could not convert time zones. A knock on my door. “Emergency call from New Zealand.” Adrenaline shot me awake. I instantly knew. It was my older brother. “Dad’s dead,” he said.

He then went on to say that he was listening to the radio and heard that a body had been found on a walking track up at Snell’s. Intuitively he called the police. It was Dad. He had climbed to the top of the hill and had a heart attack coming down. Boom. Gone. Just like that.

I knew the track that Dad had died on. No-one had to tell me, it was the one we had walked that day. Just like him to summit first and get his workout in, I chuckled to myself. Then I lay on my bed and bawled my eyes out.

* * * * * * * * * * *

My older brother and sister arrived first at Dad’s house. On the kitchen table Dad’s will and all his business papers were carefully laid out in order for us, just as Dad had arranged them before heading out on his last walk.

I arrived a few days later. Now here I was gazing upon this strange paralysed form that was my father. I scanned his room. His wedding picture, certificates from the war, a Balinese painting were on the walls. Snapshots of us, his family, on the dresser. This was what surrounded him while he slept, what mattered to him. Family, adventure, country and honour.

I was concerned that Dad might be confused, so I wrote him a letter and posted it next to his body for him to read. It said, Dear Dad, In case you are wondering what’s going on you are dead. You had a heart attack while out on your walk. We brought your body back here so that you could enjoy a family reunion. Please be with us now. On Thursday we are taking you to be cremated. When that happens it is time for you to leave. Please go to the light. Look for your Mum and Dad and brother Walter. They will be there to show you the way. You need to go so that when we die you will be there to meet us and show us where to go. We all love you. You did a good job of your life. I am so proud of you. Lorraine.

The darkness of night and the candlelight made Dad’s room feel even more sacred and a little spooky. Separated from the rest of the house by a small hallway, this room and another small bedroom hung cold with the stagnant mist of death. Everyone else had commandeered the rooms on the other side of the house for their sleeping quarters. My older sister and I reluctantly took the small adjoining bedroom to Dad’s. We felt he might be lonely otherwise. Each night she and I would take vigil by his bedside. We would talk to Dad, looking up as if he was floating around on the ceiling somewhere. On the third night it occurred to me to ask for a sign. “If you are here Dad can you let us know by flickering the candle.” On cue the candle flickered vigourously, and then the wax cracked violently. We both jumped. Dad was with us.

On the morning of the reading of the will we all gathered around the table. About to commence, the door to the hallway to Dad’s bedroom suddenly swung itself wide open. We all looked in disbelief. There were no windows open, no breezes in the house. “Dad has come to join us,” I said, and everyone chuckled nervously.

His will was simple. All divided equally, no squabbling, body to be cremated.

We all nodded agreeably except my older brother. Dad had never been fair he said. All this really belongs to our mother. As he spoke I could see he was getting worked up. Suddenly he was on his feet ranting, “I don’t want any of his money! He was nothing but a selfish bastard. I hate him!”

Bang!! We all leapt to our feet, scared out of our wits by the slamming of the hallway door. Dad had left in disgust, and we knew that he was deeply offended.

That night a huge storm came up and the wind blew at the windows. No-one slept well. It was as if all the rage and darkness that my Dad had carried in his earthly body was released into the ethers. In the morning everything was peaceful, almost serene. It felt different in Dad’s room. Lighter. Perhaps now his spirit was at peace.

We gathered around his Dad’s casket for our farewells. This day he was being cremated. We took turns to say what we wished to him. My mother read a letter to him. “Dear Gordon” her voice quivered, “today we say goodbye to you. I know that we had some hard times together. You often said that you felt that you had wasted your life. And yet when I look about me in this week here I can see that you lived a very full and successful life. I look at all our wonderful children here, six of them, all healthy and intelligent, all doing well in their lives in their own special way and contributing to make the world a better place. I can see that nothing has been wasted. Thank-you for our life together. It has all been worth it, all of it. Wherever you are I wish you the peace and happiness that often eluded you in this life. Love, Maisie.” Then she tucked the note at his feet and the lid was closed.

Dad was loaded into my brother’s van with the Sportswide logos splashed across the sides. With the coffin lying across the two back rows of seats four of us squeezed at the sides for the ride to Auckland. We felt the expense of a hearse was unnecessary. Dad would have told us we were wasting his money. Do it yourself, he would have said. On the motorway, people did double-takes to see a coffin through the window and we giggled. Dad would have liked that. It reminded us of the time he bought a Shetland pony for us kids and used to transport her around in the back of his car.

We pulled up to the chapel to take the space of an elegant black hearse that was just leaving. A small gathering patiently waited as five muddy mountain bikes were lifted from the back-rack of the van in order to unload the coffin.

The cremation service was short and sad. We cried as we left the chapel, knowing that our larger than life, funny, fighting, enigmatic father would soon be reduced to ashes and vacuumed into a little box.

The next morning a gift-wrapped Gordon was taken on the last lap of his final odyssey to Putaruru where he belonged. We arrived at the Putaruru Timber Museum for the service. I was overwhelmed by the turnout. The place was packed with his friends, relations and those who may not have loved him, but respected him, and would miss his indomitable personality in their lives.

When I spoke I told everyone how, when we were running, Dad would tell me, “Now when I die, I want to be cremated. Hire a small plane and fly over the Putaruru Borough Council while they are having a meeting. When they all come out to see what this plane is doing, throw my ashes out. As they wipe their eyes they will say, “Moller to the bitter last!” Everyone laughed, especially the councilors. They knew Dad loathed bureaucracies and relished bugging them relentlessly to get his own way. During his thirty-five years in this little highway town Dad had built up many businesses, bought and sold land and developed flats and shops and had butted many heads in doing so.

Last stop was the Lorraine Moller Reserve for the committal of Dad’s ashes. The Mayor announced that Dad had requested last month that he wanted to be buried there under a monkey puzzle tree, “It’s kind of prickly, like Gordon,” he added and then giggled as if he’d said something naughty.

The tree site was on the side of a steep hill and my mother had to dig her high-heels into the sheep ruts to steady herself in order to empty the cremains in the hole. As she shook the box a wind came up and blew the ashes straight into the faces of the crowd viewing below. The mayor and other councilors, I noted, were wiping specks of Gordon out of their teary eyes.

* * * * * * * * * * *

I have dreamed of Dad twice since he died, vivid dreams where we have talked about life after death. He told me that his actual death was “bloody horrible.” He was disorientated at first and didn’t like it at all. He misses his family. “Reincarnate as my child”, I offered, “you could even be a girl if you want and I will be your parent.” He didn’t seem as keen on this idea as I was and politely replied that he would consider it for later but right now, he told me proudly, he was busy with his university studies.

The next time we talked he was off to Australia to do work for the Aborigines. He was looking forward to that. Then I remembered to ask him what I was burning to know. “Dad, who was the man following you around, the Grim Reaper? Was he there when you died?”

“Oh yes. He was there alright. Thoroughly decent chap. He was on the Leander with me you know. Caught the torpedo. Tells me he’s been looking after me ever since. Never knew it. Just thought I was lucky.”

Then with that old glint in his eye he told me he loved me and was gone.